Imagine taking a guided tour to a famous palace, wandering away from your group, and finding yourself time-slipping to an earlier age…

Sounds like the latest Diana Gabaldon book? Or something from a science-fiction movie?

According to two scholarly ladies, Charlotte Ann Moberly and Eleanor Jourdain, this incident happened to them on a grey summer day in 1901 in the gardens of Petit Trianon, Marie Antoinette’s bijoux ‘farmhouse’ at Versailles. Miss Moberly was the head of the recently-formed Oxford women’s college of St. Hugh’s. Miss Jourdain was under consideration to be her assistant. They were on holiday, traveling through France and no doubt, wearing Jaeger wool next to the skin. They were proper, tidy, and well-respected women, products of the Victorian age, just ended that January.

Visiting the Palace, they found it uninspiring. The day was overcast and Versailles responds best to sunny days. Rather than stay, they decided to look for the Grand Trianon, the smaller ‘retreat’ of French kings. Following their Baedeker guidebook (which no proper British woman would have dreamed of travelling without – as seen in A Room With A View), they found it closed, so went on to see La Petite Trianon, where Marie Antoinette had played so charmingly at being a shepherdess – while the world beyond her gates fell apart. The ladies took a wrong turning. This is not a difficult thing to do…the lanes are long, the avenues resemble each other strongly, and there are a great many of them. At some point, the ladies became lost not only in place, but in time.

Passing a deserted farmhouse with some implements in the yard, noticing a house where a woman shook a white cloth out of the window, our time-adventurers became aware of a curious dark feeling of dread creeping over them. The landscape flattened, as the breeze died away. They saw a woman and a girl posed in the manner of a ‘tableau-vivant’ – ‘a game of mannequins’ that was quite popular in the late-Victorian and Edwardian period. They met several ‘gardeners’ in green coats and a man sitting in a garden folly glared at them, a man with a dark complexion much marked by smallpox scars. A younger, attractive man came up to the ladies, telling them they are going the wrong way over a bridge and should return to the house at once. Finally, they passed close by a lady, clad all in flowing white, with copious fair hair, sketching in a garden, just before a man bursts out of a side door, seemingly in a state of excitement.

Moberly and Jourdain walked around the house, feeling the oppression on their spirits lifting, meet up with a merry wedding party and return to Paris to finish out their holiday. Peculiarly, they don’t discuss anything that happened during that odd hour. Not until they are home again at their college, after several months have passed, do they compare notes, discussing ‘the sketching woman’ which only Moberly had seen. Why are their accounts so different?

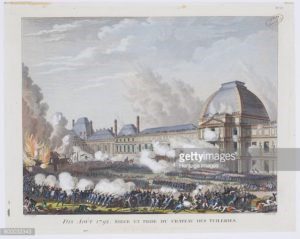

Upon further comparision, they found that Moberly had seen several figures that Jourdain had not. They decided to write up their accounts separately to keep from influencing each other any further. Upon researching the history of the time – a period which neither woman had any great experience with beyond whatever they’d learned as girls – Jourdain pinned down the day they’d ‘visited’ as being the last occasion in which Queen Marie Antoinette had been at her favorite retreat before the French mob attacked, massacring the Swiss Guards (‘the gardeners in the green coats’ which turned out to be the uniform of the rank-and-file Swiss Guards). They find a copy of a portait of the Queen, which Moberly immediately recognizes as ‘the lady sketching in the garden’, even to her attire of a white ‘old fashioned dress’ with a green scarf over it.

Still confused by the incident but becoming increasingly convinced that something out-of-the-ordinary had occurred, Jourdain returned to Versailles in January of the following year. Everything was different. The paths were not the same. The small bridge they crossed on the advice of the attractive young man wasn’t there. The haunting mood of despair was absent. Had it been some memory of the Queen’s lingering in this place – the memory of the tragedy that was about to unfold? Or had they really crossed the line between their own time and 1789?

From approximately the end of the Crimean War until the 1950’s, Britain seemed obsessed with spiritualism. With the deaths of so many young men in ‘Queen Victoria’s Little Wars’ and the cult of mourning that had grown up in the years after the death of the Prince Consort, it was not surprising that many people tried to make contact with those who had ‘Passed Over’. The popularity of the Fox Sisters in America prompted anyone with a ‘psychic feeling’ to make the attempts themselves or to put themselves in the hands of ‘mediums’ who promised to make contact for them. Naturally, there was fraud.

To mitigate that and to bring some kind of ‘scientific method’ to ghost-hunting, the Society for Psychical Research came into being in 1881. At first consisting only of 20 members, it soon grew, claiming in it’s membership many famous people of the era as well as less exalted persons. However, the SPR’s emphasis on exposing fraud wherever it occurred caused a schism as some thought they’d lost sight of their original purpose.

Both Moberly and Jourdain were members of the SPR. Therefore, when they separately wrote up their ‘adventure’, they naturally sent a letter to the SPR. The response was not favorable. They put the matter aside but it kept niggling at them. They decided to conduct their own investigation into the physical reality of Versailles in 1789. As they did not already possess knowledge about this, if it proved that the things they’d experienced had existed at the time, then they’d have evidence of their experience. It took ten years during which they’d identified the Queen, the ‘glaring man’ as the Comte de Vaudreuil and the ‘gardeners’ as members of the doomed Swiss Guards, more than a thousand of which were killed that day and more who perished later in prison or under the guillotine.

In 1911, An Adventure was published under the names of Morison and Lamont. The book detailed the incident and all their corroborative evidence. It was an instant sensation. Discussion raged far and wide, some calling it fraud, others believing every word. It wasn’t until they died that their true identities were revealed. Their being such respected scholars (Jourdain had succeeded Moberly as head of the college) gave an extra level of veracity to their account.

Until, that is, research determined that they’d altered their original 1901 accounts later, in light of their historical investigations. Had they, consciously or unconsciously, falsified their accounts to strengthen their case? Or had they mutually encouraged each other to remember more as time went on? Certainly it’s not unknown for witnesses (or family members) to ‘confabulate’ as time goes on – creating memory which becomes indistinguishable from what really happened.

Furthermore, later in life, Miss Moberly took a turn toward the religiously mystical, publishing works on Christian visionaries. She also claimed to have seen the Emperor Constantine in the Louvre. Miss Jourdain also later reported visions of times past. She eventually became so erratic in her behavior that she began to damage the reputation of St. Hugh’s. She passed away in 1924; Moberly not until 1937 at the age of ninety-one. However, it would be wrong to let knowledge of their later behavior influence a dispassionate look at the incident which bears their names.

Most who believe their report think of it as an example of retrocognition. Instead of moving *physically* through time to the final days of the French monarchy, they entered psychically into a memory of the Queen’s – the last day before the peace and ease of the Queen’s personal retreat would be shattered by the mob. Though this is not an unfamiliar phenomenon to anyone who has ever experienced ‘déjà vu’, the fact that two people seem to experience it simultaneously puts the Moberly-Jourdain Incident into a category of its own.

A final note: Later in her life, Miss Jourdain returned alone to the gardens of Versailles, trying once more to retrace those steps. Again, she saw nothing unusual until the very end of her visit where she felt once more the air of looming dread and dark sorrow. Rather than go deeper into the moment, she fled, ostensibly in order not to miss her tram back to Paris. But who would blame her if instead she felt, perhaps justifiably, that to go alone into that moment might mean no return to her own existence? I know that I would not care to wander about by myself on a grey August day at La Petite Trianon.

A reprint of An Adventure under the title ‘Ghosts of Versailles’: https://www.amazon.com/Ghosts-Trianon-C-Moberley/dp/1440448361/

An in-depth examination of the events and the persons involved: https://www.amazon.com/Mysterious-Paths-Versailles-Investigation-Psychical-ebook/dp/B01N9D50JR

Miss Morison’s Ghosts, starring Dame Wendy Hiller: http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0124008/